Unit 04: Functions I

Contents

Unit 04: Functions I#

Authors:

Dr Claire Hobday and

Dr Antonia Mey

Email: claire.hobday@ed.ac.uk

Learning objectives:#

This session is split into two notebooks both discuss how to use and write your own functions.

Functions I (This notebook)

understand inbuilt functions

understand the format of a function

input into functions

using loops and conditionals in functions

calling a function

Functions II (Next notebook)

getting information out of a function

how to write reusable code

write functions to interrogate data

Table of Contents#

Links to documentation#

Jupyter Cheat Sheet

To run the currently highlighted cell and move focus to the next cell, hold ⇧ Shift and press ⏎ Enter;

To run the currently highlighted cell and keep focus in the same cell, hold ⇧ Ctrl and press ⏎ Enter;

To get help for a specific function, place the cursor within the function’s brackets, hold ⇧ Shift, and press ⇥ Tab;

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Recap of Previous Sessions#

DDC_concepts = Mentimeter(vote="https://www.menti.com/insert_your_link")

DDC_concepts.show()

Learning outcomes of Unit 2:#

Interact with a Jupyter notebook

Declare variables

Print Variables

Getting help

Read data from a file

You will be using the following concepts:

Variables

In-built functions such as

print()

Learning outcomes of Unit 3:#

1. What is a function?#

Functions are blocks of reusable code used to perform a specific task usually more than once in a program. We have already been using some of Python’s inbuilt functions such as print(), len() and range().

When we run the command

print("Hello")

Python uses code that has already been written by someone else to output “Hello” to our screen. The command

len("Hello")

tells Python to run already written code that counts the number of characters in the string “Hello”.

These functions are inbuilt into Python, meaning they are always available for us to run from our code. However, we can also define our own functions so that we can reuse pieces of our code throughout our programs.

Reusing code not only makes our programs shorter and more organised, it makes our code easier to maintain as we only have to modify the single function rather than find and edit the code wherever we have performed the specific task.

The concept of functions can be hard to grasp for beginners. So let’s start with a simple function to print the string “Hello” and then we’ll slowly introduce more complex functionality.

A simple function#

A simple function to print “Hello” is shown in the following code.

# Define the function called "say_hello()". The function, when called, prints "Hello".

def say_hello():

# Call the inbuilt function "print()" to output the string "Hello".

print("Hello")

Why wasn’t “Hello” printed when you ran this code?

This is because all we are doing is defining a function called say_hello(). That is what def stands for. When we define a function it is saved in computer memory ready to be used (like a variable).

In order to get the function to do something we need to call it by using its name with the parentheses.

def say_hello():

print("Hello")

# Call the function "say_hello()".

say_hello()

How functions work#

Let’s explain the syntax of a function definition. The line

def say_hello():

tells Python that what we are about to do is define a function called say_hello(). The parentheses are necessary as will become clear later. The colon is also necessary.

The next line is

print("Hello")

which calls the inbuilt function print() that simply prints “Hello” to the screen. The important thing here is that the line is indented. Which means that it is inside the function. Any code lines that are indented below def are inside that particular function.

If you un-indent the print("Hello") statement you will get an IndentationError just like for conditional statements and for loops (try it).

The end of the function occurs at the first non-indented line after def.

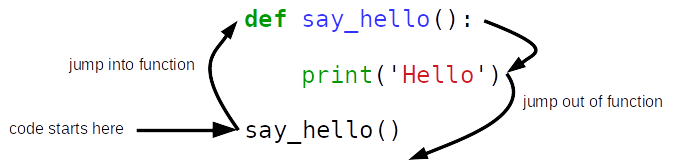

When we call a function, Python jumps into the function and executes the commands inside it. Python then returns to the end of the call. The figure below shows the order of execution of lines of code for the say_hello() function.

Notice that the program begins execution at the first non-indented line just after the function definition. When we call say_hello() the code jumps into the function at the line def say_hello():. It executes the print("Hello") function (which entails jumping into the inbuilt code of the print() function which we cannot see but is there in computer memory). It then returns from the function to the next line in the main code (which in this case is the end of the program)

Functions must be defined before they are called#

In the following code the function hi() is called before it is defined. If you run it you will see it gives a NameError because Python has not saved the function’s definition in memory when it was called.

Task:#

#FIXME

hi()

Click here to see solution to Task 1.1

def hi():

print(f"Hi")

2. Docstrings can help understand what a function does#

There is a special way of adding a comment at the start of a function to say what the function does. These are called docstrings. They are enclosed in triple quotes as shown in the following code.

You should always add a doc-string to any of your functions, however simple they may be.

def say_hello():

"""Print the word 'Hello'"""

print("Hello")

Doc-strings are used by Python to provide documentation to users. You can get documentation on any of Python’s functions by typing

help(function_name)

So if we type

help(say_hello)

Python prints out the doc-string in our function.

help(say_hello)

As you will find, the documentation of inbuilt functions assumes quite a high degree of knowledge about Python. So it’s better to use online websites to help you code.

help(help)

Some other helpful tips before starting the exercises#

In-built functions#

Let’s test out a cool in-built function called input(). This is useful if you want to interact with your code.

num = input ("Enter number :")

print(num)

Formatting outputs#

Something called f-strings provide a concise and convenient way to embed python expressions inside string literals for formatting.

str1 = "Chemistry"

str2 = "Science"

print(f"Everyone knows {str1} is the best {str2}.")

import datetime # module

today = datetime.datetime.today() # class.subclass.function()

print(f"{today: %d %B, %Y}")

# %B = full name month

# %d = day of the montth

# %Y = year full i.e. 2020 not 20.

data = {"name":"Claire", "section":"inorganic"}

print(f"{data['name']} works in {data['section']}")

Tasks#

Don’t forget the doc-string.

def string_length():

#FIXME

# Now calling the function

string_length()

Click here to see solution to Task 2.1

def string_length():

""" This function prints the length of string 'Hello'"""

# Get the length of the string Hello

length = len("Hello")

# Pring the length to screen

print(f"The length of the string 'Hello' is: {length}")

Hint: Use the built in function input() to read input from a cell.

def hello_me():

#FIXME

# Now calling the function

hello_me()

Click here to see solution to Task 2.2

def hello_me():

"""Print 'Hello name'"""

name = input("Enter your name: ")

print(f"Hello {name}")

def multiply_two_numbers():

#FIXME

# Now calling the function

multiply_two_numbers()

Click here to see solution to Task 2.3

def multiply_two_numbers():

"""Enter two numbers and print their product"""

x = float(input("Enter a number: "))

y = float(input("Enter a number: "))

print(x*y)

3. Passing values (arguments) to functions#

The say_hello() function in the earlier was a bit pointless. We called it to call the print() function to print “hello”. We could have simply written print("Hello") without bothering to define and call our own function say_hello().

Functions become useful when they perform the same task on different values passed to them. For example, say we want to write a function to print “Hello” followed by someone’s name, but the name can be different each time we call the function. We can do this by passing a value to the function. The technical name for the value passed to the function is an argument.

This is precisely what we do when we call print() or len(). For example, print("Hello") passes the string argument “Hello” to the function print() to output to your screen.

Let’s change the say_hello() function to take someone’s name as an argument.

def say_hello(name):

"""Print 'Hello' followed by name"""

print(f"Hello {name}")

# Call the function "say_hello()" twice with different names.

say_hello("Harry")

say_hello("Hermione")

We’ve changed the definition of the function so that we can pass an argument to it like so:

def say_hello(name):

name is called a parameter which is a variable in a function definition.

When we call say_hello("Harry") with the argument "Harry", the string "Harry" is assigned to the parameter name when the code enters the function. This means when we do

print(f"Hello {name}")

the function outputs Hello Harry.

When we call say_hello("Hermione") with the argument "Hermione", the string "Hermione" is assigned to the parameter name so the function outputs Hello Hermione.

Note the convention of having f" in our print statement. This is called an f-string. Using this triggers our code to know that the variable in curly brackets {name} will change to take the place of what we set that variable to, e.g. "Harry" or "Hermione" in our print statement.

Variables can be arguments#

In the above example we passed a string to say_hello(). But we can also pass a variable to a function.

But first, let’s make a new function, that’s a little more sciency than printing names.

The function below will convert a temperature in fahrenheit to celsius, which takes one argument temp

def fahr_to_celsius(temp):

"""convert fahrenheit temp to celsius"""

return ((temp - 32) * (5/9))

freezing = 32

fahr_to_celsius(freezing)

boiling = 212

fahr_to_celsius(boiling)

Note how we have to execute these in two separate cells to return the answer, otherwise the final use of the function will be the only one which is returned. Also note that the argument passed to the function (e.g., freezing or boiling) does not need to have the same name as the function’s defined parameter (e.g., temp).

A more elegant way might be to looping through a list of temperatures and calling fahr_to_celsius() for each one.

An example is shown in the following code, note that we need to print the output to screen.

# Loop through a list of temperatures

# "temperatures" is the iterating variable.

for temperatures in [32, 212, 177399]:

# Call "fahr_to_celsius()" for each "temperature"

# and "print" the response.

print(fahr_to_celsius(temperatures))

Lists and dictionaries can be arguments#

As well as passing strings and numbers to a function, lists and dictionaries can also be passed.

The function length_of_my_strings() below has a list as a parameter. It prints the length of each string in the list by looping through it.

def length_of_my_strings(list_of_strings):

"""print the length of a list of strings"""

for name in list_of_strings:

print(f" The lengths of the string is {len(name)}")

length_of_my_strings(["inorganic", "organic", "physical"])

Functions can take more than one argument#

The say_hello() function has one parameter. But functions can have any number of parameters.

Let’s rewrite say_hello() to take two arguments: a first name and a surname.

def say_hello(forename, surname):

"""Print 'Hello' followed by forename and surname"""

print(f"Hello {forename} {surname}")

# Call the function "say_hello()" with two strings.

say_hello("Harry", "Potter")

# Call the function "say_hello()" with two string variables.

first_name = "Dobby"

family_name = ""

say_hello(first_name, family_name)

In the first call, forename is assigned the value "Harry" and surname the value "Potter".

In the second call, forename is assigned the value "Dobby" and surname is assigned an empty string.

reverse_string() which prints the reverse of a string passed to it.

The call to the function is already included in the following code cell. You just need to write the function. (Look back to Unit 2 on how to manipulate strings!)

def reverse_string:

#FIXME

reverse_string("eiruC eiraM - .ssel raef yam ew taht os ,erom dnatsrednu ot emit eht si woN .dootsrednu eb ot ylno si ti ,deraef eb ot si efil ni gnihtoN")

Click here to see solution to Task 2.1.

def reverse_string(s):

"""Print reverse of string"""

print(s[::-1])

average() that takes a list as an argument and prints out the average values in the list.

def average(x):

#FIX ME

Titre_values = [22.2, 23.3, 22.3, 22.4, 22.4, 23.0, 22.0, 22.1, 21.9]

average(Titre_values)

Click here to see solution to Task 2.2.

def average(x):

"""Average of a list of numbers"""

print(sum(x)/len(x))

multiply_two_numbers() that prints the product of two number passed to it.

def multiply_two_numbers(n1, n2):

#FIX ME

n1 = float(input("Enter a number: "))

n2 = float(input("Enter another number: "))

multiply_two_numbers(n1, n2)

Click here to see solution to Task 2.3.

def multiply_two_numbers(n1, n2):

"""Product of two numbers"""

multiplication = n1*n2

print(f"{n1} multiplied by {n2} is: {multiplication}".format(n1=n1, n2=n2, multiplication=multiplication))